About Mini-Lessons for Teaching

A first grader burst through the classroom door one September morning carrying a treasure in a jar. “Look what I found last night! It’s a monarch caterpillar.” We all gathered around the jar to examine the tiny creature within. As we watched the caterpillar over the next several weeks, we saw it grow and change into a chrysalis. One day during morning meeting, one of the children noticed that the chrysalis, now a transparent covering over the butterfly growing within, was starting to crack open. Carefully, I set the jar down in the middle of our circle. Lying close together on our stomachs, we held our breath and watched the miracle of a monarch butterfly emerge. As my students and I watched with wonder, I couldn’t help but think that teaching and learning are much like the metamorphosis of a monarch. As teachers, we guide our students through many changes so that, one day, they can emerge and fly off into the world. Seeing children’s faces light up when they learn something new is as miraculous as witnessing a butterfly take flight for the first time.

WORKSHEET & Sample PDF Activity

[adinserter block=”2″]

Sample PDF Activity

[adinserter block=”3″]

From the Authors

Change can be unsettling, but sometimes it is change that leads us to open new doors and make new connections. We were faced with this opportunity when restructuring occurred in our district. Through new classroom assignments, we found ourselves teaching in the same building for the first time. We began the year teaching beside each other and grew to teach with each other.

This book evolved out of our shared belief that young children need opportunities to experience and explore nonfiction. Traditionally in primary grades, literacy instruction revolves around fiction. Our shared vision was to provide our students with supported opportunities to interact with nonfiction so that it became as natural as reading fiction.

As we began our teaching of nonfiction, our students became our teachers. It was through their eyes that we were inspired to design, share, and adapt the collaborative work of this book.

Just as we’ve enjoyed our journey of learning together, we now invite you to use these ideas and make them your own as you and your colleagues open new doors to the world of nonfiction for young learners.

What the Research Says About Teaching Nonfiction

Young children are filled with wonder. They want to know how the world works and what their place is in it. It’s a child’s natural curiosity in the world around him that is supported through reading nonfiction. The research is clear: Young children can interact successfully with informational text. (Dreher, 2000; Duke, 2003; and Duke, Bennett-Armistead, and Roberts, 2002; 2003; as cited in Duke and Bennett-Armistead, 2003)* Children can learn to read at the same time they are reading to learn!

Often because of the challenging vocabulary in nonfiction, books in this genre are reserved for use in upper elementary grades. We expect our fourth- and fifth-grade students to begin to use reading more as a way to obtain information. They are now “reading to learn rather than learning to read.” (Chall, 1983; as cited in Duke and Bennett-Armistead, 2003) Standardized tests often require a student to read a nonfiction passage and answer questions. But when do we teach them how to read nonfiction? It is important that young learners have experiences with nonfiction text so that later they can access this text with ease. The many features of nonfiction that can make it difficult to follow are also the same features that can instantly pique a young reader’s curiosity—colorful pictures, bold titles, diagrams, maps, and captions. These can provide young readers with a unique motivation and natural engagement, which is essential to the reading process. (Gambrell, 1996; Guthrie and Wigfield, 2000; as cited in Duke and Bennett-Armistead, 2003) Additionally, the fact that information can be acquired from any part of the book without necessarily having to follow the sequence of beginning, middle, and end is very freeing to many young readers.

When primary teachers understand what their students will encounter in later grades, they can lay the foundation that supports that learning. The nonfiction reading and writing that happens in primary classrooms does not and should not mirror the kinds of reading and writing going on in the upper elementary grades. Just as the caterpillar needs to eat and eat and eat before transforming into a chrysalis and then a butterfly, the primary classroom provides our young readers with the nourishment that will sustain them later.

Teaching Tip

Research conducted with kindergartners and second graders found that children can engage in research with text when they are given support. (Korkeamaki and Dreher, 2000; Korkeamaki, Tiainen, and Dreher, 1998; as cited in Duke and Bennett-Armistead, 2003)

How to Use This Book

With ongoing exposure to nonfiction materials, students will naturally become experienced with accessing facts and information to help them become experts on a topic. You can easily embed intentional teaching of nonfiction features in your yearlong literacy program to enhance students’ overall literacy skills. There are different approaches you can take with the lessons in this book to accomplish this goal.

Teaching Features of Nonfiction as a Unit of Study: You may use the lessons in this book to teach features as part of a cohesive unit of study. You might then culminate students’ knowledge by having each student create a “Features of Nonfiction” reference book, or compile one as a class, adding pages with each new lesson. (See “Your Students as Researchers and Writers,” page 84.)

Teaching Features of Nonfiction in Conjunction With Research Projects: Researching with young learners provides many meaningful opportunities to teach and revisit the various features of nonfiction. For example, students may undertake research to explore a science topic or investigate an interest. It is important for you to understand your desired outcomes before you proceed much further with your students. Focusing on the product of the research is the immediate goal. By including supports for all levels of learning, you also enable students to spend time gathering information, building information webs, organizing facts, and becoming “experts” on a given topic. Through this process students naturally build reading and writing skills. (Schiefele, Krapp, and Winteler, 1992; as cited in Duke and Bennett-Armistead, 2003) Use the materials in this book in any order to teach whole-class or smallgroup lessons on features of nonfiction as various opportunities arise.

Teaching Tip

It is also valuable to consider using the process of research as the focus for young learners. Identifying and following the steps of research—choosing topics of interest, selecting appropriate resources, accessing the information, organizing it, and sharing it—are in themselves literacy tools for young learners. Confidence as a researcher grows out of becoming a self-reliant learner.

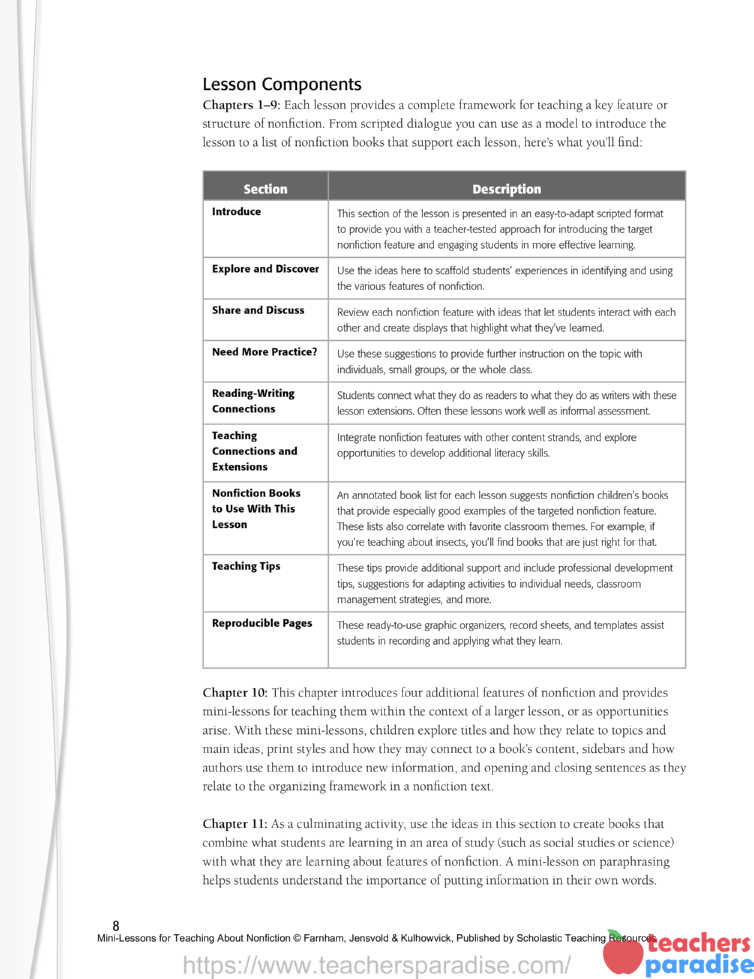

Lesson Components

Chapters 1–9: Each lesson provides a complete framework for teaching a key feature or structure of nonfiction. From scripted dialogue you can use as a model to introduce the lesson to a list of nonfiction books that support each lesson, here’s what you’ll find:

Chapter 10: This chapter introduces four additional features of nonfiction and provides mini-lessons for teaching them within the context of a larger lesson, or as opportunities arise. With these mini-lessons, children explore titles and how they relate to topics and main ideas, print styles and how they may connect to a book’s content, sidebars and how authors use them to introduce new information, and opening and closing sentences as they relate to the organizing framework in a nonfiction text.

Chapter 11: As a culminating activity, use the ideas in this section to create books that combine what students are learning in an area of study (such as social studies or science) with what they are learning about features of nonfiction. A mini-lesson on paraphrasing helps students understand the importance of putting information in their own words.

Connections to the Language Arts Standards

The lessons in this book are designed to support you in meeting the following language arts standards as outlined by Mid-continent Research for Education and Learning (McREL), an organization that collects and synthesizes national and state K–12 curriculum standards.

Reading

- Uses reading skills and strategies to understand a variety of informational texts.

- Uses mental images based on pictures and print to aid in comprehension of text.

- Uses meaning clues to aid comprehension and make predictions about content.

- Understands level-appropriate sight words and vocabulary.

- Understands the main idea and supporting details of simple expository information.

- Makes contributions in class and group discussions.

- Asks and responds to questions.

- Summarizes information found in texts.

- Relates new information to prior knowledge and experience.

Writing

- Writes (or uses emergent writing) in a variety of forms or genres and for different purposes.

- Uses writing and other methods to describe familiar persons, places, objects, or experiences.

- Generates questions about topics of personal interest.

- Gathers and uses information for research purposes.

- Uses strategies to compile information into written reports or summaries (for example, incorporates notes; includes facts, details, explanations, and examples; uses diagrams or other visual aids).

Chapter One

Getting Started With Nonfiction

I sat with a basket of books balanced on my knees. The basket, which we labeled earlier in the year, reads “Fantasy.” “If you were choosing a book from this basket, what kind of book might you expect to find?” I ask a curious group of first and second graders. “Storybooks,” “picture books,” “fantasy books,” and “books that are make-believe” are some of the responses I get. I pick up one of the books for all to see. “What if I choose this book to read?” I read the title and author, The Gingerbread Baby by Jan Brett. “What are some things you would find in this book?” My students know the book well and are eager to respond. They are very familiar with fiction.

“Today we are going to begin learning about another type of book.” I have collected an assortment of nonfiction books, which I have loaded into a red wagon. I wheel the wagon into the middle of our circle. The children are immediately excited because all the books are hardcover and rather thick looking, very much like books that only a “good reader” would use. Suddenly, the children are on their knees, leaning in, eager to touch the treasures in front of them.

Introduce: What Is Nonfiction?

Lead students through a brief introduction to nonfiction, using the script below as a guide. Then provide time for children to discover and explore nonfiction books they choose. They may spend time reading a favorite, focus on particular pages, or take a “picture walk” through several to see what interests them most. (See Explore and Discover, below.) Then bring students together to share. (See Share and Discuss, page 12.) The sample dialogue provided gives you an idea of what to expect: Students will be eager to share fascinating details and comments about the books they’ve just explored.

“What about these books?” I ask, as I pull several out of the wagon and place them in our circle.

“They’re about real stuff!” exclaims Will.

“They probably have facts in them,” adds Rachel.

“That one’s about dinosaurs. Can I have that one?” Connor can’t wait to get his hands on the book.

“They’re nonfiction,” declares Alex.

“That’s right,” I say. “These books are called nonfiction books. We’ve been reading lots and lots of storybooks.” [I point to the fantasy basket.] “You know a lot about reading fiction. You know about characters, problems, and solutions. You know about stories having a beginning, middle, and end. Today I’d like you to choose nonfiction books to read.”

Teaching Tip

Just as it is important to give children time to explore new math materials, they also need time to browse and explore new genres of literature. Before introducing formal lessons on features of nonfiction, give children time to dive in and see what they can discover about nonfiction on their own.

Explore and Discover

My direction is simple: “While you read, think about what’s special about nonfiction. We’ll share our discoveries at the end of our reading time.”

Children can hardly wait to get started, and the classroom quickly becomes abuzz with “Ooohs!” and “Aaahs!” and “Wow! Look at this!” Soon there are clusters of students reading together and talking about the neat things they are learning.

As students select and explore nonfiction books from the class collection, circulate among them and ask questions to guide their discoveries:

Why do you think the author wrote this book? What do you think you might learn by reading this book?

How do you think the author gathered information to write this book about [topic]? What resources do you use to get information about topics you’re interested in?

How is this book like other books you’ve read? How is it different?

Share and Discuss

As we regroup, the sharing is animated. My students are eager to share the information they learned.

“Did you know there is a jellyfish that is about three times as big as a man?” William says, holding up a diagram he found while reading about the ocean.

“I found a T. rex,” reports Mark.

“And I found frogs that were all different colors!” adds Emma.

It is clear that children’s curiosity is captured by the information in the books. They have already experienced success—skipping over sections that don’t interest them or make sense to connect with random facts of interest. The feeling of power that comes from being able to access information has already begun to build each child’s confidence as a reader.

“Wow, you learned a lot today while you were reading!” I pause, then continue, “I’m wondering something. Why do you think people read nonfiction?”

“To learn new things,” they respond.

“And why do people read fiction?” I wonder aloud.

“I read fiction because it’s fun to read a story, and I read nonfiction to learn new stuff. That’s fun, too!” says Caroline.

I have set the stage for a comparison of fiction and nonfiction. We spend the next few days becoming familiar with nonfiction books. My role during this time is to help children notice features as they arise. One way to do this is to use a Venn diagram to compare and contrast fiction and nonfiction. (See Reading-Writing Connections, page 13.)

Need More Practice?

Children enjoy sorting and classifying, and this is one way to provide further practice in identifying characteristics of nonfiction texts. Place an assortment of fiction and nonfiction books in baskets. Invite children to work with partners or in small groups to sort them, using what they know about both genres to place the books in two groups: Fiction and Nonfiction. As children classify the books, encourage them to compare features of fiction and nonfiction. What are some clues that a book is fiction? For example, as children flip through pages of a book, they might notice the illustrations and ask themselves, “Could this really happen?” To go further, students can classify nonfiction books into categories such as informational, how-to, “true stories,” and biographies.

Reading-Writing Connections

Using a Venn Diagram

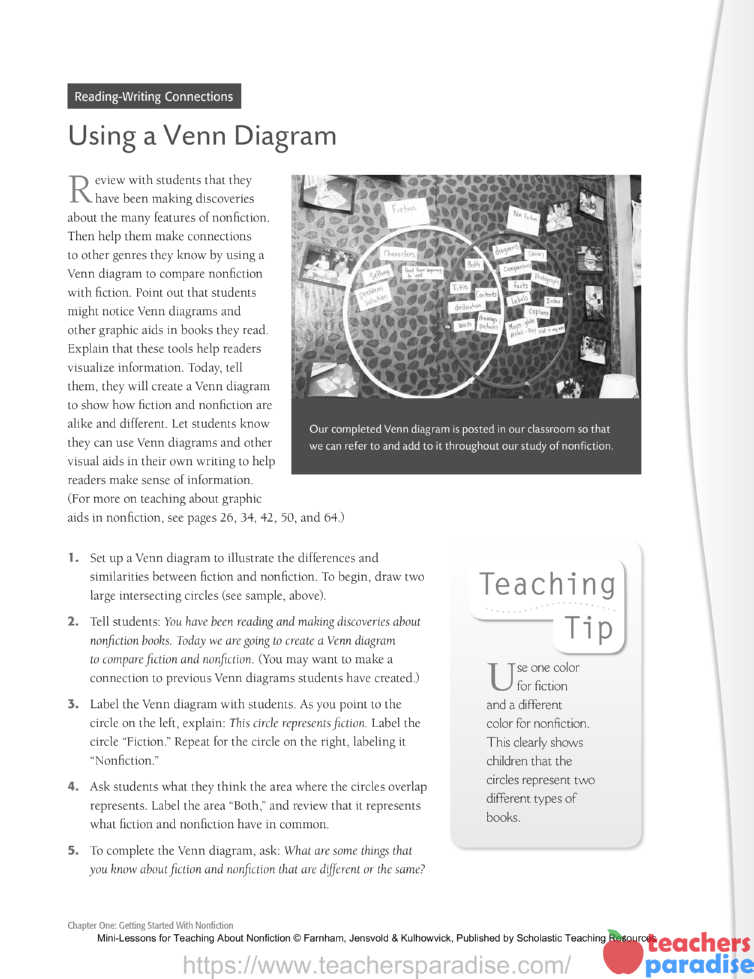

Review with students that they have been making discoveries about the many features of nonfiction. Then help them make connections to other genres they know by using a Venn diagram to compare nonfiction with fiction. Point out that students might notice Venn diagrams and other graphic aids in books they read. Explain that these tools help readers visualize information. Today, tell them, they will create a Venn diagram to show how fiction and nonfiction are alike and different. Let students know they can use Venn diagrams and other visual aids in their own writing to help readers make sense of information. (For more on teaching about graphic aids in nonfiction, see pages 26, 34, 42, 50, and 64.)

- Set up a Venn diagram to illustrate the differences and similarities between fiction and nonfiction. To begin, draw two large intersecting circles (see sample, above).

- Tell students: You have been reading and making discoveries about nonfiction books. Today we are going to create a Venn diagram to compare fiction and nonfiction. (You may want to make a connection to previous Venn diagrams students have created.)

- Label the Venn diagram with students. As you point to the circle on the left, explain: This circle represents fiction. Label the circle “Fiction.” Repeat for the circle on the right, labeling it “Nonfiction.”

- Ask students what they think the area where the circles overlap represents. Label the area “Both,” and review that it represents what fiction and nonfiction have in common.

- To complete the Venn diagram, ask: What are some things that you know about fiction and nonfiction that are different or the same? Responses may include: “Fiction is not true and nonfiction is true.” “Fiction is a story.” “Fiction has a beginning, middle, and end. You can read nonfiction in any order.” “Both have an author.” “Both have a title.” The list goes on and on. Record responses in the appropriate areas of the Venn diagram.

- Display the Venn diagram and review with students that presenting the facts this way (as opposed to in paragraph form) helps readers more easily make sense of the information.

Teaching Tip

Use one color for fiction and a different color for nonfiction. This clearly shows children that the circles represent two different types of books.

Teaching Connections and Extensions

Students may be surprised at the many places they can find nonfiction. Invite them to look around the room for examples. They may find it in books on shelves and in baskets, in charts and graphs on the walls, in newspapers on your desk, on a map posted by the door, in instructions for games, in their science textbooks, on the Internet, and elsewhere. Take opportunities to make connections to nonfiction in daily activities—for example:

- in science, as children read and follow steps for conducting an experiment or analyze data on a weather graph.

- in social studies, as children read and learn about people, places, and their environment.

- in physical education, as children review posters on the wall about healthy habits.

- in math, as children read explanations about how to solve a problem.

- in print around the room that informs students of the daily schedule, reminds them of class expectations, charts reading strategies, and so on.

Nonfiction Books to Use With This Lesson

To introduce a study of features of nonfiction, gather any collection of nonfiction that you think will capture your students’ interest. Following are a few suggestions, each of which also offers young readers an introduction to the particular features of nonfiction covered in this book.

Amazing Animal Facts by Jacqui Bailey, Joe Elliot, and Jayne Miller (Dorling Kindersley, 2003): This popular classroom resource combines fascinating facts with photographs to engage and inform young readers.

Biggest, Strongest, Fastest by Steve Jenkins (Ticknor & Fields, 1995): From a tiny flea to the mammoth blue whale, this book of records invites children to compare and contrast animals’ characteristics to their own.

Houses and Homes (Around the World Series) by Ann Morris (Lothrop, Lee and Shepard, 1992): Vibrant full-color photos take readers around the world to see how people in different places live.

Martin’s Big Words by Doreen Rappaport (Hyperion, 2001): This Caldecott Honor pictorial biography of Dr. Martin Luther King’s life features a time line of important dates.

The Post Office Book: Mail and How It Moves by Gail Gibbons (Thomas Y. Crowell, 1982): Follow a letter from the time it is dropped in a mailbox until it reaches its destination.

Tell Me Tree: All About Trees for Kids by Gail Gibbons (Little, Brown, 2002): Vivid illustrations and labels help young readers learn how to identify trees.

This Land Is Your Land by Woody Guthrie (Little, Brown, 1998): Students may find themselves singing along to the familiar lyrics as they learn about America’s history and geography.

Throw Your Tooth on the Roof: Tooth Traditions From Around the World by Selby Beeler (Houghton Mifflin, 2001): Explore traditions around the world with a playful look at what happens when children lose their teeth.

Waiting for Wings by Lois Ehlert (Harcourt, 2001): “Out in the fields, eggs are hidden from view, clinging to leaves with butterfly glue.” A favorite feature of this book is the mini-book within the book that tells the story of caterpillars. Pages grow in size as the butterflies emerge.

Wake Up World! A Day in the Life of Children Around the World by Beatrice Hollyer (Henry Holt, 1999): The author compares and contrasts to take readers through a typical day in the lives of children around the world. A large map lets readers locate where each child lives.

Table of Contents

From the Authors – 4

About This Book – 5

What the Research Says About Teaching Nonfiction – 6

How to Use This Book – 6

Lesson Components – 8

Connections to the Language Arts Standards – 9

Chapter 1: Getting Started With Nonfiction – 10

Chapter 2: Contents Page and Index – 16

Chapter 3: Diagrams – 26

Chapter 4: Captions – 34

Chapter 5: Speech Bubbles – 42

Chapter 6: Maps – 50

Chapter 7: Glossaries – 58

Chapter 8: Time Lines – 64

Chapter 9: Comparisons – 72

Chapter 10: Integrating Additional Text Features – 80

Chapter 11: Your Students as Researchers and Writers – 84

Final Thoughts – 95

ISBN-13: 978-0-439-85656-0

ISBN-10: 0-439-85656-6