A Parent’s Guide to Promoting Reading, Writing, and Other Literacy Skills From Birth to 5

Introduction

We’ve all seen the PSAs. Movie stars, athletes, and politicians encouraging us to read to our children. Read to our children. Read to our children. We get it: We should read to our children! Unfortunately, though, 15-second public service announcements too often leave us asking, “What am I supposed to read?” “How am I supposed to read?” “When am I supposed to read?” “Are there activities besides reading that will boost my child’s literacy?” And, most important, “Why does this matter so much?” Hopefully, this book will answer all those questions, as well as make you realize that you are already doing a great deal to support your child in making literacy an important part of his life.

WORKSHEET & Sample PDF Activity

Sample PDF Activity

What This Book Won’t Do

Although this book is crammed with useful ideas and information about developing literacy, it will not show you how to teach your child to read in 100 easy lessons before she is 3. It will not give you evidence to claim that your child is the best and brightest at the day care center. It will not allow you to skip getting that teaching certificate and become your school district’s literacy coach. In a nutshell, the book is not a magic bullet but a useful tool to help you understand what is going on as your child is growing and how to support that growth.

What This Book Will Do

This book is designed to help you, the interested parent, learn more about the seemingly magical process of literacy development. It will provide you with the guidelines you need to assist your young child in developing the skills and understandings that will allow him to make literacy a lifelong, enjoyable endeavor.

You will learn to develop a literacy-enriched environment for your child by thinking about the materials you provide and the access your child has to those materials. You will think about the role that literacy plays in your own life and discover ways to show how important it is to your child. Through this book, you will learn the critical aspects of literacy that can be developed birth to 5 and what you can do to address them.

We help you consider many ways that literacy already touches your life and your child’s—ways that you might not even be aware of. The bottom line: We teach you to enhance what you are already doing and suggest new things to do to maximize the impact on your child’s growing literacy.

How to Use This Book

This book can be read in whole or in parts. You might sit down and read it cover to cover. We’re guessing, though, that if you have young children, you won’t have time to do that! So feel free to read it in chapters or chunks, reflect on what you read, and revisit it. Each chapter not only addresses how to promote literacy in a different part of your home (kitchen, living room, bedroom, and so forth), but also addresses different aspects of promoting literacy, such as building vocabulary, helping children understand how books work, and making connections between letters and the sounds they represent. The book is filled with tips, checklists, and quick ideas to help you promote literacy in whatever way makes sense for you, your child, and your busy life together. However you use the book, your child’s life will be richer for it.

Even for Infants?

It may be clear why we address preschoolers and toddlers—but infants? As a matter of fact, we have evidence that infants can engage in literacy activity. Nell’s daughter, for example, turned the pages of Melanie Walsh’s board book Do Monkeys Tweet? at 3 months, and laughed at parts of Eric Carle’s The Very Busy Spider at 6 months—and Nell has the video to prove it. Indeed, by the end of infancy, many children growing up in literacy rich homes can pretend to read books, make letter-like marks (in finger paint, perhaps), and, most important, show a strong interest in reading and writing materials. Therefore, throughout the book, we discuss developmentally appropriate literacy-rich environments and activities for infants.

What Are Those Symbols?

Throughout this book, we use the convention of showing the sounds in words by using letters bracketed by slashes—for example, when we mean the sssss sound we’ll represent it like this: /s/. If we mean the letter itself, we’ll use s. So we could say, for example, that the letter c sometimes stands for the /k/ sound and sometimes stands for the /s/ sound.

Chapter 1 – Literacy and the Young Child

When You Say “Literacy,” What Exactly Do You Mean?

Long ago, being literate meant being able to sign your name! Over time, the definition of literacy grew to mean the ability to read enough to get by in life and work, to write a little, and that was about it. As more time has passed, and society’s demand for literacy has increased, that definition has changed radically. Literacy has come to mean reading, writing, listening, speaking, gaining meaning from pictures by viewing, and communicating ideas by visually representing them.1 The current concept of literacy encompasses much more than knowing the alphabet or being able to sound out words; in fact there are many children who can do those things but can’t understand what they are reading, communicate effectively through writing, or use language to meet their needs or accomplish their goals. Later in this chapter we share specific literacy goals for children according to age, but fundamentally, we’re concerned with developing skills in reading, writing, listening, speaking, viewing, and visually representing, from the first moments babies can hear and see us. (See the section entitled Why Start So Early With Literacy? on page 15.) Regardless of your child’s age, if he is growing in his ability to read, write, listen, speak, view, and visually represent, he is becoming literate, or developing emergent literacy. (See What Is Emergent Literacy? to the left.) The purpose of this book is to help you foster emergent literacy.

What Is Emergent Literacy?

Emergent literacy refers to the point in children’s development before they become conventionally literate—that is, before they can read on their own or write text that others can read.2 The concept assumes literacy learning begins at birth and develops or emerges gradually over time. There is no magic moment when children suddenly “are readers and writers.” They are always becoming readers and writers. Unlike “reading readiness,” this view maintains that children are born ready to learn about literacy and continue to grow in their literacy understandings throughout life. Understanding emergent literacy is important for parents because it implies that the extent to which you support your child’s literacy development in the early years of life is critical and consequential to success in later life.

Literacy Development Begins at Birth

Educators used to believe there was a particular age when children were “ready to read.” One study, published in 1931, even determined this magic age to be 6.5 years.3 But more recent thinking suggests that literacy “emerges” from birth, given exposure to a literacy-rich environment. Long before children can read and write in the conventional sense, they are learning about literacy.4 Specifically, they are learning why, what, and how people read.

Why People Read

Children first learn about literacy and its functions from the people around them. As your child’s parent, you show her daily the many reasons for interacting with text. For example, when you bring in the mail, you might say, “I wonder what came today.” You might find a letter from Grandma, a circular from the supermarket, a couple of bills, and a clothing catalog. Let your child see you read the letter, find out what’s going on with Grandma, and maybe laugh at a funny story she tells. Let her see you read the circular, cut the coupons from it, and perhaps make a list of items to purchase. Let her see you pay the bills by writing a check, and let her look at the catalog herself. A single mail delivery provides many opportunities to show different reasons for reading and writing.

What People Read

Look around and notice all the different kinds of reading materials available to us—books, magazines, newspapers, Web sites, labels, signs, and so many others. Don’t be surprised if your child is already aware of these materials. One of our favorite illustrations of how much young children can learn about different types of texts is from a 3-year-old child who scribble-wrote two texts—one with short scribbles in a narrow column down one side of the page, another with long scribbles that extend across the page. She identified the former as a shopping list and the latter as a story! Already she knew something about these two different kinds of text. (See samples to the right.)

How People Read

Children begin to learn about how we read as early as infancy. Specifically, they develop concepts of print, or an understanding about how print “works,” alphabet knowledge, comprehension skills, and other literacy knowledge and abilities. For example, they learn that we:

• Read (English) from left to right and top to bottom

• Identify words by looking at their letters, which in turn represent sounds in speech

• Use different parts of the text—such as words, illustrations, graphics, and the context of reading—to help us make meaning

(For further discussion of children’s growing knowledge about how to read, see Chapter 3.)

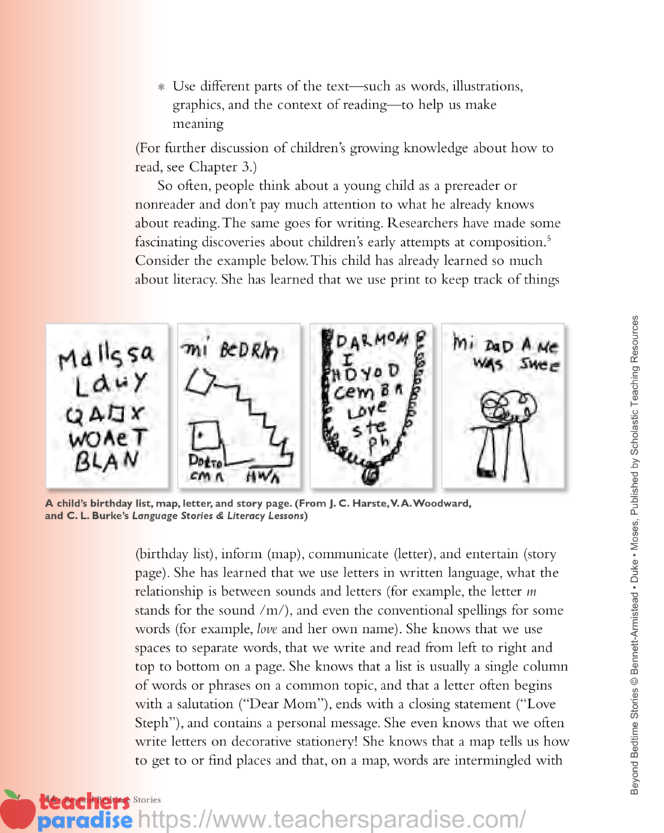

So often, people think about a young child as a prereader or nonreader and don’t pay much attention to what he already knows about reading. The same goes for writing. Researchers have made some fascinating discoveries about children’s early attempts at composition.5 Consider the example below. This child has already learned so much about literacy. She has learned that we use print to keep track of things (birthday list), inform (map), communicate (letter), and entertain (story page). She has learned that we use letters in written language, what the relationship is between sounds and letters (for example, the letter m stands for the sound /m/), and even the conventional spellings for some words (for example, love and her own name). She knows that we use spaces to separate words, that we write and read from left to right and top to bottom on a page. She knows that a list is usually a single column of words or phrases on a common topic, and that a letter often begins with a salutation (“Dear Mom”), ends with a closing statement (“Love Steph”), and contains a personal message. She even knows that we often write letters on decorative stationery! She knows that a map tells us how to get to or find places and that, on a map, words are intermingled with graphics. In contrast, on her story page, she separates the words and the graphics, but maintains a thematic relationship, as story writers often do. And this analysis doesn’t even cover all this child knows about literacy! Take a look at your own child’s writing, and don’t be surprised if there’s a lot more to it than you initially believed.

Why Start So Early With Literacy?

Why is it so important to provide literacy-rich environments and activities for young children? Why should we put them on the road to reading and writing as early as infancy? Here are five reasons, although there are undoubtedly many more.

Literacy Can Enrich Your Child’s Daily Life

Just as print plays an integral role in your life, it can play an integral role in your child’s life as well. For example, name labels can identify your child’s clothing, room, and artwork. Labels and pictures can indicate where materials and toys are stored. A list of your child’s favorite foods can be used to plan meals together. Reading aloud daily can be engaging for children—just as engaging as dressing up, building with blocks, or playing on a jungle gym. Literacy is so embedded in the homes featured in this book that it is impossible to imagine what life would be like without it.

Literacy Can Be a Source of Great Joy for Your Child

For generations children have enjoyed wonderful books such as The Snowy Day by Ezra Jack Keats, The Runaway Bunny by Margaret Wise Brown, first-word books, and many others. We have never met a preschooler who did not respond with glee to the playful book Tumble Bumble by Felicia Bond. We have never met an infant who was not captivated by Margaret Miller’s Baby Faces. Many adults can still tell you their favorite children’s book. In fact, certain children’s authors, such as Dr. Seuss and Maurice Sendak, conjure up so much nostalgia, they have become a permanent part of adult popular culture. All children have a right to the joy that books and beloved authors can bring.

Literacy Provides a Way for Your Child to Learn About the World

Books and other print materials can help children explore and better understand the people, places, and things that they encounter in everyday life. Print can also help children learn about the bigger world beyond their immediate one. Children on a farm in Iowa can learn about people who live near the ocean in California. Children who live in the United States can learn about the history and culture of people in China. Children everywhere can learn about dinosaurs, the moon, and life underground. Literacy, like nothing else, puts the whole world in children’s hands.

Literacy Knowledge Is an Excellent Predictor of Your Child’s Later School Achievement

Children who know alphabet letters and the sounds they represent, who can hear sounds in words, who have richer vocabulary and concept knowledge, and who understand how print works are far more likely to be good readers in kindergarten and in the grades that follow.6 And this connection is not just coincidental but causal. Providing stronger literacy education for children in the early years has been shown to lead to better outcomes for them later on.

Literacy Builds Knowledge About the Way Language Works

Books and other print materials are important tools for building children’s vocabulary. Our language contains many words and complex structures that children may not learn unless they are exposed to books and other print materials. Everyday oral language often does not include all of the words and language structures we find in written text. Consider the following passages from two children’s books:

Tiptoeing with solemn face,

with some flowers and a vase,

in they walked and then said, “Ahhh,”

when they saw the toys and candy

and the dollhouse from Papa.

From Madeline by Ludwig Bemelmans

Something big stirred underneath her. Daisy shivered.

She scrambled up onto the riverbank. Then something

screeched in the sky above!

From Come Along, Daisy! by Jane Simmons

These books, each appropriate even for toddlers, have wonderfully rich vocabulary and sentence constructions. Hearing books like these helps children develop powerful and sophisticated language that will be important to them in their own writing in later schooling, in their careers, and in other communications.

The arguments for weaving literacy into young children’s environments and activities are multiple and strong. However, some educators and parents worry that introducing literacy is not developmentally appropriate for young children. As you might guess, we disagree.

What Should You Expect to See as Your Child Grows From Infant to Kindergartener?

If we agree that literacy begins developing right from birth, a next logical question is, What should we expect from children at different ages? What should children know and be able to do in literacy when they leave infancy and enter toddlerhood? Leave toddlerhood and enter preschool? How about by the end of preschool? Having the answers may help you engage your child in developmentally appropriate activities and build on her emergent literacy (as will reading this book, we hope).

ISBN 13: 978-0-439-89231-5

ISBN 10: 0-439-89231-7

Table of Contents

Acknowledgments – 4

Foreword – 5

Introduction – 7

Chapter 1: Literacy and the Young Child – 10

Chapter 2: Literacy Throughout the Day – 26

Chapter 3: Literacy Throughout the Home – 38

Chapter 4: In the Kitchen – 64

Chapter 5: In the Living Room – 90

Chapter 6: In the Bedroom – 120

Chapter 7: Literacy in Unexpected Places – 152

Chapter 8: Literacy Beyond the Home – 162

Chapter 9: Advocating for Literacy in Your

Child’s Educational Setting – 188

Children’s Books Cited – 200

Endnotes – 203

Index – 206