Literacy in Grades 3 to 6: Where Do We Stand?

For some years now educators and policy makers alike have focused attention on early literacy and early intervention. In many places, their efforts have paid off. More young children are reading better than ever before (Forgione, 1998; Vermont Department of Education, 2006; National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), 2005). This is cause for celebration. However, an early investment in education alone cannot address the challenges of achievement in the United States, as recent findings prove. Unfortunately, getting off to a good start is not enough (Rand Reading Study Group, 2002).

Almost every recent report and summary review of literacy achievement in the U.S. suggests that Charlie is not alone. The inescapable conclusion is that children beyond grade 3 are not performing as well as we would like. Reports by E. D. Hirsch (2003) and others have dramatically labeled this long-standing phenomenon the “fourth-grade slump.”

WORKSHEET & Sample PDF Activity

[adinserter block=”2″]

Sample PDF Activity

[adinserter block=”3″]

The National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) is one of the major methods of tracking students’ literacy achievement across the country. Since its beginnings in 1969, it has been administered periodically to fourth- and eighth grade students. The most recent results, published in 2005, indicate that there was no significant change in reading performance between 1992 and 2005.

Overall, only 64 percent of fourth-grade students and 73 percent of eighth-grade students were at or above the Basic level in reading.

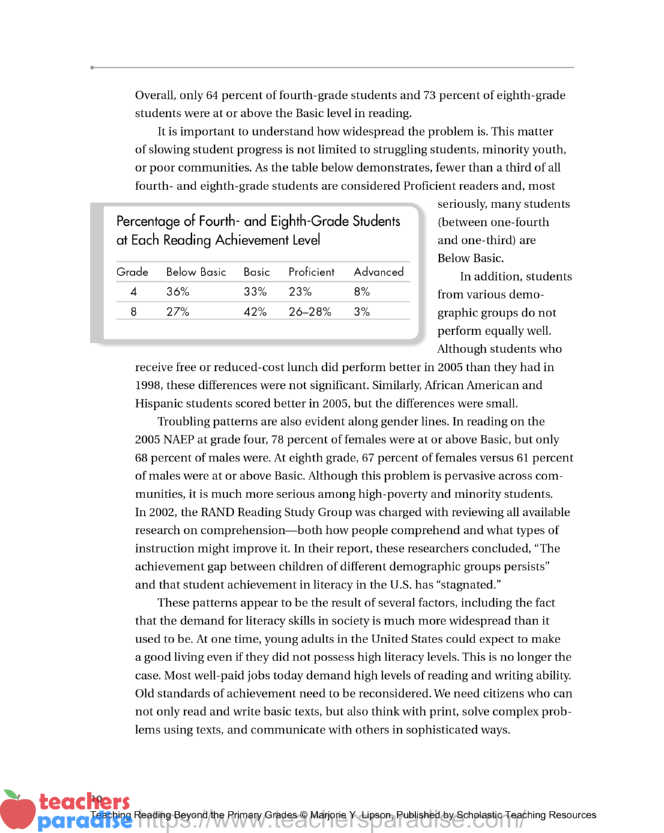

It is important to understand how widespread the problem is. This matter of slowing student progress is not limited to struggling students, minority youth, or poor communities. As the table below demonstrates, fewer than a third of all fourth- and eighth-grade students are considered Proficient readers and, most seriously, many students (between one-fourth and one-third) are Below Basic.

In addition, students from various demographic groups do not perform equally well. Although students who receive free or reduced-cost lunch did perform better in 2005 than they had in 1998, these differences were not significant. Similarly, African American and Hispanic students scored better in 2005, but the differences were small.

Troubling patterns are also evident along gender lines. In reading on the 2005 NAEP at grade four, 78 percent of females were at or above Basic, but only 68 percent of males were. At eighth grade, 67 percent of females versus 61 percent of males were at or above Basic. Although this problem is pervasive across communities, it is much more serious among high-poverty and minority students. In 2002, the RAND Reading Study Group was charged with reviewing all available research on comprehension—both how people comprehend and what types of instruction might improve it. In their report, these researchers concluded, “The achievement gap between children of different demographic groups persists” and that student achievement in literacy in the U.S. has “stagnated.”

These patterns appear to be the result of several factors, including the fact that the demand for literacy skills in society is much more widespread than it used to be. At one time, young adults in the United States could expect to make a good living even if they did not possess high literacy levels. This is no longer the case. Most well-paid jobs today demand high levels of reading and writing ability. Old standards of achievement need to be reconsidered. We need citizens who can not only read and write basic texts, but also think with print, solve complex problems using texts, and communicate with others in sophisticated ways.

To make matters worse, while the demands for literacy have accelerated, reading comprehension instruction in many schools is often minimal or ineffective (RAND Reading Study Group, 2002). In part this reflects the erroneous belief that accurate word recognition automatically leads to good comprehension (M. Y. Lipson, 2003). Thus educators and policy makers have traditionally focused attention on the word-level aspects of literacy, believing that accurate and automatic word identification would take care of any reading problems. Further, teachers beyond grade 2 often feel that they should not be concerned about reading instruction—that the primary grade teachers are responsible for this work. Unfortunately, even when students acquire high levels of word-level proficiency, they may not develop the other knowledge and skills needed to become highly literate adults (RAND, 2002).

Despite clear evidence that well-articulated literacy instruction is needed in grades 3 to 6, little attention has been focused on teaching and learning during this period. Too often, intermediate students are on their own as they negotiate the move from the primary grades, where they received daily guided reading instruction, to middle school, where they are expected to be able to read with comprehension in a variety of genres in order to accomplish a variety of tasks. What is needed is a bridge between good primary-level instruction and solid instruction for adolescents. This book is intended to lay the foundation for that bridge.

What Does Research Say About Reading in Grades 3 to 6?

It is becoming clear that students in grades 3 to 6 do not necessarily need “more of the same”—that is, a continuation of the modes of instruction they’ve received so far. To become more capable readers and writers, they need materials, tasks, and contexts different from those they received in the primary grades. “As content demands increase, literacy demands also increase: students are expected to read and write across a wide variety of disciplines, genres, and materials with increasing skill, flexibility, and insight” (Snow & Biancarosa, 2003, p. 6). Instruction for both on-level and struggling readers must respond to these changing demands. Reading in grades 3 to 6 can be viewed through two lenses: word-level concerns and text-level concerns.

Word-Level Concerns

Word-level concerns in grades 3 to 6 relate to both decoding and meaning. Most reading experts use the term “word recognition” or “word identification” to signal the ability to decode words and “vocabulary” to indicate word meanings. Therefore, when I discuss phonics or syllabication, I’ll be talking about word recognition; whenever I am addressing the development of word meanings, I’ll be talking about vocabulary.

Often young readers encounter words that are difficult to recognize, but familiar in meaning. Thus, while reading Too Many Tamales by Gary Soto, words like cousins, bright, underneath, or stomachs may be difficult for primary-grade students to decode. The meanings of these words, however, are not at all challenging. On the other hand, while reading The View from Saturday by E. L. Konigsburg, words like claim, emerge, vigor, or hybrid may be reasonably easy to decode, but their meanings may be unknown even to capable fourth-or fifth-grade readers.

Instruction in the intermediate grades must emphasize the meaning of vocabulary because researchers conclude that students who enter fourth grade with limited vocabulary are likely to experience significant reading comprehension difficulties, even if they have good decoding skills (RAND Reading Study Group, 2002). The problem is compounded by the fact that, as Andrew Biemiller points out, “current school practices typically have little effect on oral language development during the primary years. Because the level of language used is often limited to what the children can read and write, there are few opportunities for language development in the primary grades” (2003, p. 2). Even students who have relatively good vocabulary development can struggle because during grades 3 to 6 there is a dramatic increase in vocabulary difficulty.

At the same time, of course, word identification does get more difficult—even for students who have mastered phonics. In E. L. Konigsburg’s The View from Saturday, the first chapter includes words like electronic, commissioner, volunteered, counterclockwise, unaccompanied, and signifying. These words are exactly the sort of “long words” that absolutely terrify many intermediate-grade students. Even though these students probably do know (or could infer) the meanings and might be able to decode them, they often panic—saying the first word that comes into their heads and moving on with a shrug. Applying decoding skills to multi syllabic words is difficult for many students in grades 3 to 6. To make matters worse, there are also many words that are both hard to decode and unfamiliar in terms of meaning, such as benevolently, calligraphy, and domicile.

In later chapters, I explain these word-level concerns in more detail and also provide ideas for how to improve both word recognition (Chapter 6) and vocabulary development (Chapter 4).

Text-Level Concerns

There is a good research base regarding effective comprehension instruction (Block & Pressley, 2001; Dole, Duffy, Roehler, & Pearson, 1991). Yet few schools have strong programs in this area, for several reasons. First, of course, many teachers simply have not been well prepared to teach children to comprehend text. For years we believed that comprehension would occur naturally as a by-product of accurate word recognition. The idea was that if we taught children to decode and recognize words, comprehension would take care of itself. We now know otherwise. The overwhelming weight of evidence suggests that comprehension requires more than good reading accuracy (Kamil, Mosenthal, Pearson, & Barr, 2000; National Reading Panel, 2000).

The limited focus on comprehension is a problem for students at all grade levels, especially children at grades 3 to 6, since the nature of reading changes so dramatically during these years. Students need stamina and motivation to stick with much longer and more complex texts. As well, they must develop the strategies for comprehending many diverse texts for a variety of purposes, “all the while developing their identities not only as readers but as members of particular social and cultural groups” (Snow & Biancarosa, 2003, p. 7).

In the primary grades, students generally do not encounter a balanced diet of texts. Nell Duke’s important research demonstrated that young children read hardly any informational material (Duke, 2000). Fewer than 10 percent of the classroom books in primary classrooms are informational and less than four minutes a day are spent reading informational text! Clearly, in these early grades, students have limited exposure to varied types of texts. As students move into grades 3 to 6, they encounter many more nonfiction textbooks, newsmagazines, and other informational materials, all of which they are likely to find interesting, but also difficult.

Finally, the tasks that students encounter in these upper grades are also more challenging. Students are expected to answer higher-level questions, respond both critically and personally, find evidence to support their answers, make inferences about complex ideas, and connect ideas across multiple texts and contexts. Not only have they never carried out many of these tasks, they’ve probably never received instruction in how to go about them.

Teaching Reading in Grades 3 to 6: Taking the Steps to Improve Instruction

This worrying convergence of results has sometimes led to the conclusion that there is little that can be done for students in grades 3 to 6, especially for high-poverty students with few opportunities to read books and develop sophisticated oral language. Jeff Howard has rejected this type of thinking with his provocative assertion that “smart is not something you are; smart is something you get” (1995, p. 90). He argues that schools should be less concerned with how smart children are at the moment they arrive and a great deal more about how to help them “get smart” through powerful instruction and excellent, demanding learning experiences. I share his view.

This book is designed to help you acquire the knowledge and skill necessary to help students get smart. It summarizes what we know about effective literacy instruction beyond the primary grades, describing the types of classroom organization and practices needed to ensure that students achieve high levels of comprehension and sophisticated abilities to think with print.

I tell stories and share lessons from my own work and from the work of many educators and researchers. For more than three decades, I have been teaching reading and studying literacy. That work has taken place in urban, suburban, and rural schools and at universities. Many of the experiences I have had and the people with whom I have worked appear in one way or another in this book, so you deserve to know a little background about them.

I read my way to an excellent education from modest roots and I want the students with whom I work to have the same opportunity. I began teaching in a bilingual (Spanish-English) community in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and then later taught in inner-city Washington, D.C. I always taught in grades 4 to 6. I love intermediate students’ energy and emerging thinking. I like the books they read, the content they study, and their sense of humor and their willingness to take risks. Teaching them can be a joy.

I currently teach graduate and undergraduate courses and have conducted research on many aspects of literacy. For years I directed the reading clinics at two different universities. Ten years ago my colleagues and I (see M. Y. Lipson, Mosenthal, Mekkelsen, & Russ, 2004; Mosenthal, Lipson, Torncello, Russ, & Mekkelsen, 2004) began a study of unusually successful schools. In our research, we studied schools from all socioeconomic situations and added an examination of less successful schools, to be sure we could see how the two groups were alike and different. Although, affluent schools are more likely to be successful, many schools that serve high poverty populations are successful, too. (See M. Y. Lipson et al., 2004.) We spent two years in these schools, examining all aspects of their classroom and school-based programming, trying to identify key factors that distinguished successful from unsuccessful schools. Throughout the book I share those findings.

Most recently, I have been collaborating with a talented team of literacy experts to apply the lessons we learned in our study to schools that are struggling. We are working with teachers in grades 3 to 6 in an effort we call the Bridging Project.

This work, and the work of many other researchers, has shown us that there are a number of challenges facing teachers in grades 3 to 6. Organizing and managing a complex classroom that responds to the enormous diversity and range of abilities of students is one such challenge. Dealing with comprehension problems is another. Too many intermediate students are inexperienced thinkers—they cannot comprehend multiple genres and complete challenging tasks. Other students lack the prior knowledge and vocabulary to read the content area texts; this is true across all socio economic levels. And, of course, some students are still struggling with decoding or fluency. They find reading too difficult at the word level. Lack of motivation and engagement is a common problem among many students in these grades.

To complicate matters further, assessment tools and strategies that were effective and efficient for primary-grade teachers are often not appropriate for intermediate students. In addition, there is often much more mandated testing occurring at these grade levels so that teachers feel they cannot or should not do more. Thus, teachers may not have the type of assessment data that would truly help them to differentiate instruction.

Drawing on Research and Practice for This Book

Over the years, my colleagues and I have learned as much as we’ve taught. Our own research and that of others indicates that a program designed to help students “get smart” needs a number of elements. Instead of arguing about whether children should be immersed in literature or whether they should receive direct instruction, we need to accept the fact that children need both. Further, the program needs at least four relatively distinct but interacting components:

- Engagement and discussion of text within a community of learners

- A focus on conceptual development and higher-order thinking

- Instruction designed to teach comprehension and build independence

- Appropriate approaches to develop word identification, vocabulary, and fluency

These components are important for all students but they only come to fruition against the background of effective classroom organization, effective assessment, and a plan for differentiation.

Each of the following chapters in this book is designed to address one or more of the major challenges we have encountered in our work. (See Figure 1.1.) I start with organization and end with differentiation. In between, I address ways to engage students in discussion, help students comprehend both narrative and informational texts, promote students’ development of concepts and vocabulary, identify and select texts and tasks designed to help students become better thinkers, and explain how to assess reading in grades 3 to 6.

Each chapter is organized more or less the same way. In the first section, I summarize lessons from research and practice and provide both background information and instructional tools for the specific strategy being discussed in that chapter. Each chapter also includes a section entitled “Into the Classroom,” in which I provide advice and examples related to classroom implementation.

Throughout, you will find descriptions of real classrooms, examples of student work, and practical suggestions for teaching students in grades 3 to 6. Finally, each chapter closes with three brief sections: “Concluding Thoughts,” which summarizes the chapter; “Discussion and Reflection,” which contains ideas that you can use alone or with colleagues; and “Digging Deeper,” which lists resources for further information on the chapter’s topic.

Concluding Thoughts

Despite the dismal picture of performance, there has never been a better time to be teaching in grades 3 to 6. For the first time, experts from many fields are looking closely at these students, and more and better resources and supports are available to those of us who think we can make a difference.

There is still too little research, but what research there is points to the intersection of excellent work on early literacy and adolescent literacy. Drawing from that research, as well as reflecting on our own practice, we can create a reading program that makes sense for our students. And there are lots of materials available to help. There are now more informational texts for students than ever before. A wide selection of novels and short stories can motivate students and keep them engaged with fiction. And more professional resources are available to help us learn how to teach with these wide-ranging materials. In the chapters that follow I will bring new ideas and tried-and-true practices together.

Discussion and Reflection

• What do the test data say about student performance in your school/district?

• What, if any, initiatives have already been started?

• What are your greatest challenges in teaching grades 3, 4, 5, or 6?

• What do you feel is your greatest strength in teaching reading in these intermediate grades?

Table of Contents

Acknowledgments – 4

Foreword by Taffy E. Raphael – 6

Chapter 1: Literacy in Grades 3 to 6: Where Do We Stand? – 8

Chapter 2: Organize for Success: Block Scheduling, Flexible Grouping, Curriculum Planning, and Other Baseline Essentials – 20

Chapter 3: Build Community and Engage Students – 50

Chapter 4: Develop Background Knowledge, Vocabulary, and Higher-Order Thinking – 86

Chapter 5: Teach Comprehension and Build Independence – 126

Chapter 6: Extend Word Identification, Fluency, and Spelling Skills – 166

Chapter 7: Make Effective Use of Assessment – 196

Chapter 8: Differentiate Instruction to Reach All Students – 238

Professional References Cited – 276

Children’s Books Cited – 283

Index – 286